Melancholia (von Trier, 2010) and Solaris (Tarkovsky, 1972) both present Bruegel the Elder’s Hunters In The Snow (1565), but each film does it differently. In Solaris, the painting appears as part of the films diegesis, hanging on the wall of the space station’s library. In Melancholia, it appears both diegetically, in the lodge’s collection of art books, and more emphatically, extra-diegetically as one of a series of animated icons that make up the film’s overture. To what extent can we understand the intermedial relations each film creates between itself and Bruegel’s painting as expressions of the two image regimes governing each film: the Time-Image and Cinema-Hostis? Melancholia repeats several elements found in Solaris: the expressive presence of horses in the mise en scène, an alien planet as of figure human affect, references to precapitalist painting. In Melancholia, these shared elements retain visual similarity, but their semantics differ from those in Solaris’s iteration, as if to draw attention as much to the difference between the films as to what they have in common. In order to start to explore the contrasting ways films from each period use works from other art practices, one might start by sketching the differences in the way the painting’s appears in these two films.

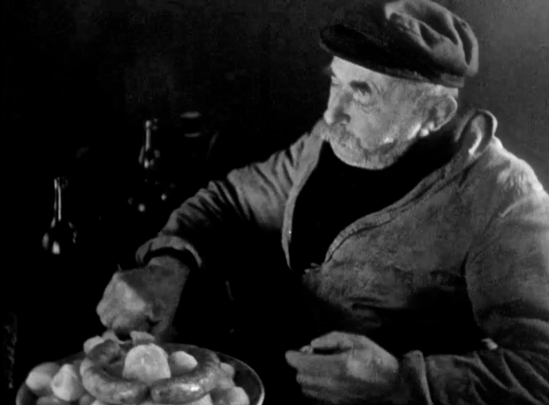

In Solaris the camera first shows Hunters In The Snow in a shot from the point of view of Hari, an avatar created by the planet Solaris in order to interact with humans. She looks at it after a sequence during which some of the crew make it clear that they do not consider her human, only a fabrication made from the Kris Kelvin’s memories. When Kelvin returns to the library after walking another crewmember out, he finds Hari contemplating the painting and joins her. Although he looks at Hari, who is gazing straight ahead, at the tail of the glance shot, his presence implicitly bifurcates the point of view. When the glance shot times later in the sequence, the eye line matches show both characters looking at the painting. In the object shots, the camera shows details of the tableau and lingers on elements of the foreground and background as if comparing them: the clear details of expression on the face of a dog accompany hunters contrast with the sketched character of flora in the hind planes of the painting. The camera avoids showing the whole canvas, as if it were too much for Hari to take in all of once, or too sublime to be grasped in its entirety. It is as if planet, Solaris, learns about humanity through a study of art performed by the person of Hari, whom Kris watches and gazes with out of love and amazement. Solaris uses Hunters In The Snow to set up a complex free indirect image bearing the subjectivities of the alien planet, its avatar Hari, who appears as a human individual, and Kris Kelvin. Solaris’s sequence of Hunters In The Snow’s contemplation functions as a compound of the disclosure of human Truth to a consciousness that knows it not, and as the witnessing of such disclosure by a human. If we note that the rest of Bruegel’s seasonally themed paintings for Niclaes Jongelinck also hang in the library, we might conclude that Hari’s contemplation discloses a specifically bourgeois truth to Solaris.

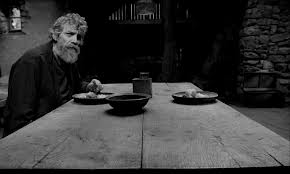

Melancholia begins with a series of moving icons or figures, referring to the moments of its narrative. Hunters In The Snow appears in the third icon, following a close medium shot medium shot of Kirsten Dunst opening her eyes with dead birds falling in the background, and a saturated shot of a sundial on a terrace overlooking the grounds of the estate. The following shot shows the painting, with the wide aspect ratio emphasizing the hunters on the left more than the original. Dark flakes begin to fall from the sky over the painting and in the implied space between the camera and surface of the canvas. When the surface of the image begins to burn, it becomes clear that the flakes are ashes rather than evening snow. After Dunst’s character, Justine, fights with her sister Claire in a room decorated with art books, she replaces the volumes displayed open to plates of supremacists paintings, with books showing classical canvases, Hunters In The Snow among them. In this sequence of Bruegel and the other classical paintings appear as fragments moving through the frame as Justine handles the books. The Maleviches appear in the background. Justine does not contemplate either set of paintings, but she moves as if she can’t stand the modernist ones. Beyond the simple irony of Malevich as decorator for a vacation Lodge patronized by top level executives, one might also note that Melancholia’s framing of the painting in the overture, emphasizing the hunters and their distance from the town to which they are returning plays on the absolute separation in the film between the super-wealthy residents of the lodge, the staff serving them, and the village.